Previously in Readers Write...

Readers Write #1 March 09

News

from the author, now and then.

Readers Write #2 May 09

Robbery in the Library, Gender Confusion, and a Dog Named 'Moggy'.

Listen, I just write the books. Who knows where they end up? I've

had mail from Norwegians on oil platforms, and from a pilot who

flies jumbos for a South Pacific airline, and from Jim in Alberta

where it's often 30 or 40 below. I'm told the U.S. Marines in

Iraq enjoy my WW2 desert story, A Good Clean Fight.

Nothing surprises me, not even the email from Tim in Australia that

began: "The first book I stole was

Piece of Cake." He

nicked it from the school library when he was 16. "I probably

read it another six or seven times before it fell apart." By then

he was old enough to pay for books, so he bought another copy.

Should have bought two, and given the other to the library.

These thoughts are prompted by the steady stream of letters (and

cheques or PayPal requests) that followed

Nicholas

Lezard's corker of a review of

Hullo Russia, Goodbye England

in The Guardian a couple of weeks ago. David in Maryland ordered a copy

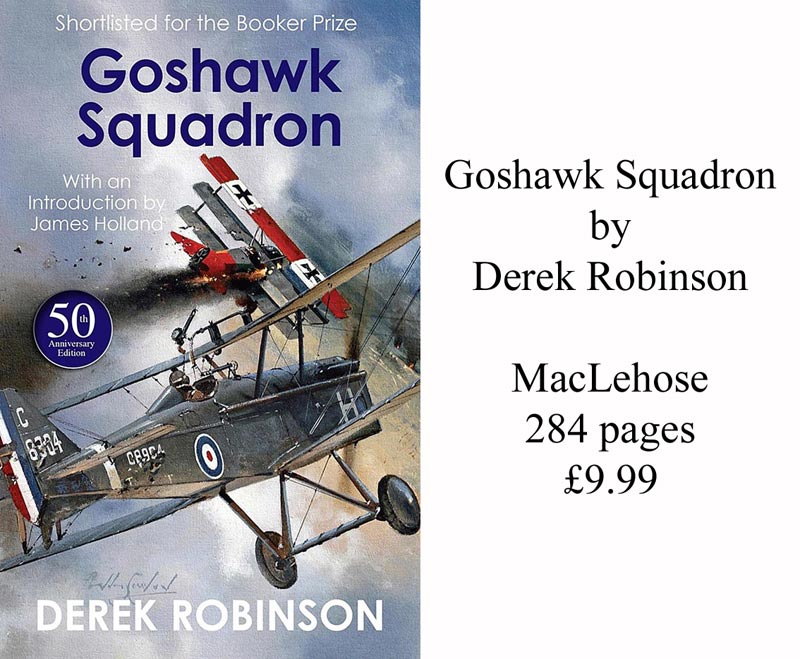

and wrote that he came across Goshawk

Squadron over 35 years ago and still re-reads it, along with other

yarns of mine. Helen in Dublin said she 'enjoyed' my writing,

then thought that 'appreciated' was a better word, and finally upgraded

that to 'enthralled'. W.B.T. in Southampton has read and re-read all my

books, and (he says) so has his wife, which is pleasing.

Paul in Dublin ranks me as "one of 3 or 4 authors all of whose work I

own"; and Matt in London "recently read

Goshawk Squadron on my

honeymoon and absolutely loved it." (Let's hope that marks the

start of a long relationship.) And many more

letters, saying more of the same, including the nice lady in

Wales who addressed me as 'Dear Sir or Madam'.

Readers Write #3 June 09

Thomas Keneally

is a very good researcher, By chance, he met the owner of a Californian

leather-goods shop who was one of the Polish Jews rescued from the

German death camps by Oskar Schindler. After that, Keneally worked hard

to find the facts that became

Schindler's Ark, which became the film Schindler's List. He

could have written another Holocaust history. Instead, he wrote his

book as fiction - not because he wasn't sure of the truth, but because

he didn't want it to end up on the packed shelves of Holocaust volumes.

Keneally wanted his story to be read by people who never look at World

War Two histories. And he succeeded.

I think I know how he feels. I parted company with one publisher

because my fiction always ended up in the Military History section of

the shop. That wasn't why I wrote it. I wrote it for the Keneally

reason, so that people might get an idea of what war is like at the

sharp end. Not the daily scores in, say, air combat in the desert war

(which is how military historians tend to see the battle) but how a

fighter squadron lives, kills and dies in the sand, flies and blood of

the Western Desert. A Good Clean Fight is good history; I

researched it thoroughly. But it takes you where the military histories

never go. I hope that's true of all my flying stuff.

Including the latest, Hullo Russia, Goodbye England. I've had

some feedback from former Vulcan pilots and groundcrew. Chris in London

flew Vulcans and said: "It was a good read, and took me back." Brad in

Lincoln said, "Have just finished it. Grand read!" Having been

front-line ground crew for 15 years, he noticed a couple of places

where I slightly bent the truth - for instance, each Vulcan airbase was

either a Blue Steel or a bomb station, but not both. My mistake.

And here's another detail I might have included: "There is no mention

of the dreaded P Tube, a rubber bladder with a fitted chrome receptacle

into which you could pee, if you really had to. After a sortie, each

crew member emptied their own, normally at the side of the Crew Chief's

hut on the pan." I suspect that's the kind of info my readers like to

know. Some people thought Baggy Bletchley bought it in a portable loo

at the end of Piece of Cake, and were pleasantly surprised to

meet him again in Hullo Russia. He survived

Cake, and A Good Clean Fight; he may surface again.

I was happy that Brad confirmed the problems of arming a Vulcan with

the Blue Steel missile. The fuel (HTP) was so toxic that any groundcrew

splashed with it had to dive into a nearby plunge bath instantly, or

his clothing caught fire. And loading the missile meant 230 gold studs

(the Butt Connector) made perfect contact; if not, download and start

again. An exercise involving Blue Steel began hours before take-off. A

far cry from the famous 'four-minute warning' of an attack.

Peter, a former Vulcan captain now in France, got the book and

wrote: "I sat in a deckchair at the week-end and I pretty much read it

straight through. I think that says a great deal, and I found it a good

read. The story perhaps stretched the imagination a little in some

areas. Certainly our hero Silk could not have been disposed of quite so

quickly." Well, endings are often the most difficult part. Peter adds

that he joined the Vulcan OCU eight years after Silk. By then, the

aircraft was a truly low-level machine, Blue Steel had long gone, and

so had the WW2 veterans in the aircrew. (Maybe some of the mindset of

those who had bombed German cities went with them.) But Peter also read

Piece of Cake. "I think you have caught the repartee and banter

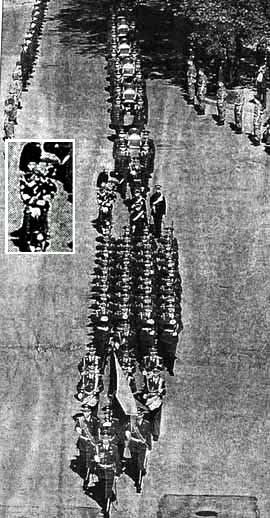

of aircrew magnificently," he says. "My first Vulcan squadron used the

Snow White party trick." (That's the one with everyone in line astern,

marching on their knees, arms folded, singing 'Hey Ho!' - it's in Cake,

page 75.) "With 55 aircrew on the squadron, there were sometimes more

than seven dwarfs!"

Thanks to all who wrote. And welcome to several public libraries who have bought copies, including Enfield (in London), Hartlepool, North Yorkshire, Dorset and Wrexham. Glad to have you on board.

No Guinness in Mongolia, a shrink's view of Silko, and "Jag tycker om det," in spades.

Amazing

how many people steal books, especially books by me. I've heard from

honest,

upright citizens who wouldn't think of cheating on the golf course, but

who

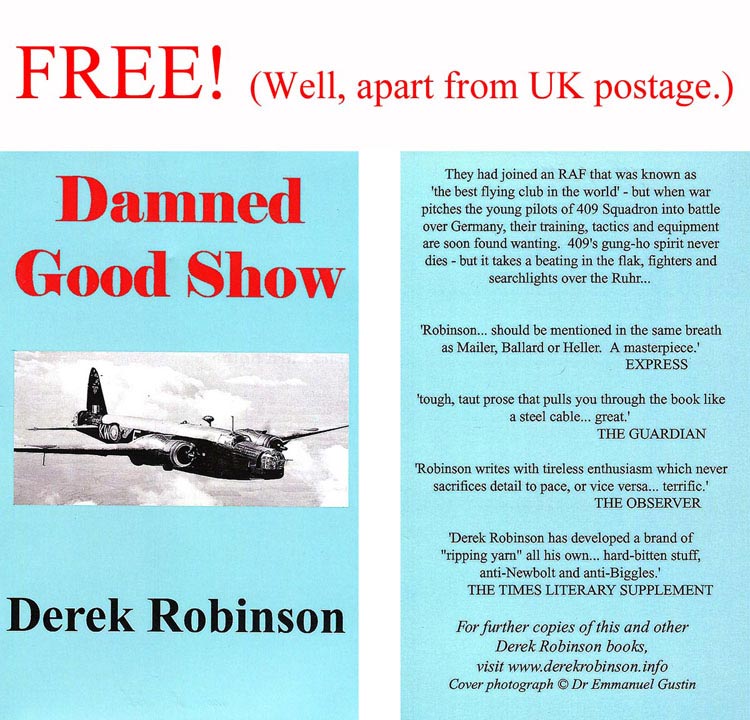

admit that they stole a copy of 'Piece of Cake' or 'Damned Good

Show'. Often it was the school or college library

that was plundered. That's how Jan in

Am I?

Aren't most

authors? Before I wrote 'Goshawk

Squadron', for instance, I worked hard on the research, and learned all

I could

about what the R.F.C. was doing in

Okay.

Now for something brighter, as they don't say on TV

news. Imagination. I

use it all the time. How it works, beats

me. I'm just grateful.

Take a story of mine called 'Kentucky Blues'. It's about a small,

not-too-bright town called

That

episode came

partly from my imagination and largely from my experience when I was

playing

for the Manhattan Rugby Club in

Quick

round-up of some readers' messages. Ron in Walthomstow

found 'Hullo

************************************************************************************

Readers Write #6 October 09

Heroics,

Tin Pan Alley, and a First from

Someone remarked

that there are no heroes in my books.

Plenty of courage, no lack of sacrifice, a lot of death. But

heroes?

The word itself has been done to death.

I was in New York when US soldiers, marines and airmen returned from

the First Gulf War, nearly twenty years ago, and they got a

tickertape

reception. New Yorkers called them all

'heroes', and many servicemen looked uncomfortable with the

label. In any army, for every frontline fighting man

there are six or seven or even ten men behind

him, providing support. Cooks,

medics, dentists, truck drivers, guys organising supplies, keeping

records,

sending signals. All doing essential

jobs, but are they all heroes? When

everyone is heroic, the word has lost all meaning. Let's save it

for those who truly deserve

it.

Moving on: I've always believed

that a good writer can

write convincingly in any style that's needed

- tabloid journalism, song lyrics,

boring bureaucratic jargon,

whatever. I'm sometimes disappointed by

crime novelists who include chunks of newspaper

reporting for the sake of plot.

They've obviously never worked on a paper. When I wrote 'The

Eldorado

Network' -

which is

about a double agent reporting allegedly secret info -

his style often had to be boring in order to be convincing. The facts seemed more exciting because the

writing was so dull. I worked hard on

that, just as I did in 'A Good Clean

Fight' where I wanted to quote the lyrics of a certain popular song. (Good contrast with the bleak

When you don't care...

I'm bound in iron bands.

When you don't care...

I'm lost in desert sands.

In this wilderness, with none but you to guide me,

I'm in heaven with your tenderness beside me...

And if you think any

fool could have written that, just try

writing the next verse. But don't steal my

words. They're my copyright now.

Fresh insights from

readers' messages. Anthony in London

bought 'Hullo Russia...' and mentions what a pleasure it is "to find a

novelist who is able to produce books that you can't put down - I

finished 'Piece of Cake' in a few days and felt totally wrung out

by the sense

of tension and fatigue you managed to sustain..." By

contrast, a different reaction from John,

somewhere in

And Richard in

Readers Write #7 November 09

Viewers are

smart, readers are far-flung,

The television adaptation of Piece of Cake still attracts questions. (It was first shown in 1988, so if you're under 25, ask your parents.) All five hour-long episodes are now available on DVD, at what strikes me (and I can be impartial because I sold the rights and so I don't make a penny from the DVD) as a very low price. If you can't find it locally, try Ian Allan Publishing - that's where I bought mine. For a drama, the TV showing pulled in a big audience. I think the final episode attracted 13 million viewers in the UK, and LWT sold the series around the world. In the US it went out on Mobil Masterpiece Theatre, a much respected viewing slot. And don't tell me they spell it 'Theater' over there. Mobil called it 'Theatre', and I have the poster to prove it.

Tim in Victoria, Australia was 12 at the time, watched Cake with his Mum, bet her that Moggy would survive, "which of course ultimately resulted in my having to make both our beds for a week." This throws an interesting light on the novel and one reason why I think it keeps on getting re-read (and re-shown): it's the unpredictable nature of events. A good story should surprise. I set out to tell the events of the Phoney War, the Battle for France and the Battle of Britain, just as they might have happened to one RAF fighter squadron. All the research I did (and that was a lot) confirmed one thing: many pilots got killed, some in battle, some not, some by inexperience, some by sheer bad luck. Flying was risky in those days. On a typical fighter squadron, of those pilots who had begun the war, most would not be flying a year later. Sometimes none.

This is the unpredictable element that keeps Piece of Cake on edge. When the television series was being cast, I was pleased to see that I recognised hardly any names. Viewers are smart. They know that the star they meet in episode one is not going to be killed in episode two or three, and probably not at all - television has paid that actor a ton of money and it's not going to be wasted. Nearly all the pilots in Piece of Cake were played by young unknown actors. Some became better known later (Jeremy Northam, Nathaniel Parker) and Tom Burlinson had already made a name in Australia but not in Britain. So viewers could never guess who would live and who would die. Tim, aged 12, guessed wrongly, and that both reflected the truth of the war and upheld the dramatic tension of the story. Incidentally, I thought Neil Dudgeon, who played Moggy Cattermole, was excellent. An RAF fighter pilot who actually led a squadron in the Battle of Britain read the book, saw the series, and wrote to me. He had known men like Moggy, and he summed him up very neatly: "Bad for discipline, good for morale - every squadron should have one. Just one."

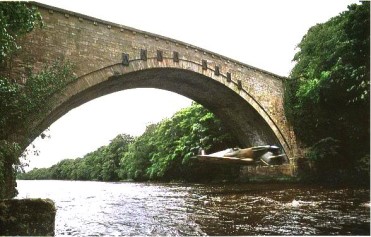

Other questions I get asked: (1) Did I write the screenplay? No, I didn't. I'd put four hard years into the novel, and I was very happy when Leon Griffiths (who created Minder) wrote the screenplay. (2) The novel says Hurricanes, so why use Spitfires? Very few Hurricanes survived, and none were aerobatic, so it was Spits or nothing. (3) Did I like the TV version? Well, naturally I pefer the book, but it's a long story and if they'd shot the whole of the printed word, the series would never have ended. It's pretty good. The music is haunting. I wish it were on CD.

Back to readers write. Among the more exotic messages have been those from Bernice, who runs Crooked Timber Books in what sounds like a very rugged corner of Nova Scotia; Jarmo in Finland (ordering the RFC trilogy); Anette in Sweden (ditto); plus Karen in Switzerland (Hornet's Sting), Jules in Holland, Charles in Prague and Werner in Vienna (all for Hullo Russia, Goodbye England).

Which prompts two thoughts. First: that I'm lucky to write in English, a global language. When an Egyptian airliner talks to Bulgarian air traffic control, they talk in English. I'm sure Finland is a delightful country, but if I'd been born there, writing in Finnish would not have made my career any easier. And my second thought is that there are translations of my work sitting on my shelves that might make an unusual gift if you have a friend in another country. I have copies of Goshawk Squadron in French (Les Abattoirs du Ciel), in Spanish (Escadrilla Azur), and in Dutch (Het Havik Squadron). There's The Eldorado Network in Spanish (El Spia Dorado) and in Dutch (Het Eldorado Netwerk); and Kramer's War in Finnish (Luutnantti Kramerin Sota) and in what may be Belgian but is probably Dutch (Kramer's Oorlog). I've even got Polish versions of A Good Clean Fight (Pustynny Ogien), and of The Eldorado Network (Siatka Eldorado) and of Artillery of Lies (Artyleria Klamstw). If you're interested, email me and we'll take it from there.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Readers Write #8 December 09

Rumblings in Cornwall, the Forgotten War, and three helpings of 'Cake'

I sense a smouldering impatience in Cornwall. K.M.D. of St Ives writes to say how much he's enjoyed my previous books, especially the RFC/RAF trilogies. 'Damned Good Show' meant much to him because his father-in-law was in Bomber Command in WW2, got shot down in a Wellington, spent four years in Stalag Luft III, and then in the 1950s instructed at RAF Finningley, a V-Bomber base. Which is why K.M.D. particularly wanted to read 'Hullo Russia, Goodbye England' - it echoes much of his father-in-law's experience.

But then he adds: "I've been disappointed that there aren't more of your RAF books. After all, there's still a lot of WW2 left for Hornet Squadron after 'A Good Clean Fight', and there's also Korea, Suez etc."

Well, I wish I could oblige. The money would be nice. I see other writers who, year after year, produce a succession of novels that play variations on the same tune, and a small voice inside me says: Why don't you do that? Dick Francis writes a horse-racing novel a year. His fans love him. Write an RAF novel a year and your fans will love you. Why not? And a loud voice inside me says: Because you'll be bored rigid. Even the great Conan Doyle grew to loath Sherlock Holmes and tried to kill him off. His fans wouldn't wear it and Doyle went back to grinding out more variations on a tune that must have made him want to throttle someone. If not Holmes, then Watson. Or Inspector Lestrade. Or Mrs Hudson.. Or, ideally, the whole gang.

I'm not in the grinding-out business. I write novels because I find an idea that strikes me as different, even surprising. I try to write a story that I enjoy - something fresh and unusual, maybe something that upsets what most people think they already know. Every novel is a gamble. I like risk. So I can't do what K.M.D. of St Ives suggests, which is to put Hornet Squadron into Suez or Korea simply because those wars happened. I need an idea as well, a hook to hang the story on.

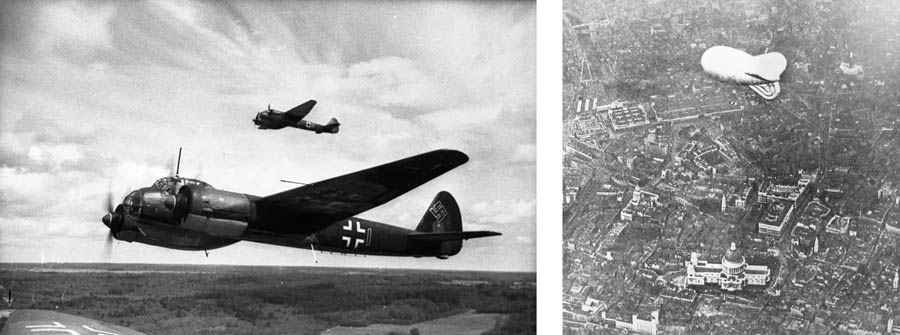

One of the hooks I found, and used in 'Damned Good Show', is the forgotten war waged by Bomber Command from the outbreak of war to 1941/2. Say 'Bomber Command' to most people and they think of Lancasters flattening German cities. But the Lancs weren't much seen on ops until mid-1942, and not in large numbers until 1943. Take the Thousand-Bomber Raid on Cologne on 30th May 1942; only 73 Lancs took part in that, as compared with 79 Hampdens, 131 Halifaxes and 602 Wellingtons (plus others). In fact, Bomber Command's first operation was on the very day that war was declared, 3rd September 1939. During the next couple of years, the Command learned how (and how not) to take the battle to the enemy homeland.

So I was very pleased to hear from someone who was there at the start. Lawrence Wheatley in Bude, Cornwall. He qualified as an Air Observer (soon to be renamed Navigator) in summer 1939, and joined 'B' Flight of 144 Squadron. The squadron flew Hampdens, a compact twin-engine bomber that plays a big part in 'Damned Good Show'. Lawrence suffered from chronic air-sickness and was grounded by the medics, which almost certainly saved his life, because on 29 September 1939 'B' Flight was searching for targets north of Heligoland and ran into German fighters. All five Hampdens were shot down. Soon people were calling it the 'Phoney War'. It was real enough for the RAF. Throughout WW2, Bomber Command losses were heavy. Of the 48 men who completed Lawrence's Air Observer course, 28 died in action or in flying accidents.

Lawrence said he's enjoying D.G.S., "though slightly disappointed" that it's centred on the officers "and little is said about the Sergeants' Mess where the majority of the crew would live." It's a fair point. My problem was numbers. I told the story through the pilots, who were usually officers. That involved a dozen (or more) characters. If I had included the Sergeants' Mess too, it would have doubled the cast. That would be more than I, or most readers, could handle.

Meanwhile, my other flying stories have been prompting some mail. Bob in Ottery St. Mary flew Canberras and Buccaneers (both types were capable of carrying nuclear weapons) and he writes: "I don't know how you do it, but the atmosphere and the characters on the squadrons I've served on are often reflected in your books." Steve in Nottingham, having just read 'Hullo Russia, Goodbye England', says: "The flying descriptions - absolutely brilliant. I presume you leaned on some former pilots to get that right." Well, I certainly had my stuff doublechecked for accuracy, but in essence it all came out of what's left of my mind. Chris in the Borders "liked HRGE immensely. You have a way with character dialogue that, in my opinion, is second to none....Also the story had me from the start; these are characters that I may not necessarily care about, but I revel in their ups and downs, and ultimately they mostly win me over by the end; including Luis Cabrillo from 'The Eldorado Network' trilogy..." (It's actually a quartet, with the new book 'Operation Bamboozle', which Chris bought.) Jonathan in Basingstoke is now on his third copy of 'Piece of Cake', having worn out the other two: "Still an old favourite that I revisit every few years....and it has the rare gift of giving something different every time." While Susan of Colchester bought HRGE and 'Hornet's Sting' as a Christmas gift for her husband, "a devotee of your writing"; and when Richard in Kent got his copy of 'Operation Bamboozle', he was "really chuffed to have a shelf full of your produce." And I'm chuffed too.

***********************************************************************************************

Readers Write #9 February 2010

Barrel-rolling a Boeing, our forgetful MPs, and a nice line in scams.

For the filming of Piece of Cake, the Spitfires were flown by professionals, and they took it seriously, which is understandable when (a) the aeroplane was worth half a million pounds (more now), and (b) it was irreplaceable, and (c) your life depended on it.

Nevertheless, I remember a day when the weather was too gloomy for filming, and one pilot got very bored with hanging around. When the cloud-level lifted the light was still poor, but he was itching to fly, and so he took off and threw his Spit around for ten minutes. Just for fun. No charge on the producers. But the pilot got a big charge out of it.

I mention this because I imagine that inside every commercial pilot is the ghost of a fighter pilot who sometimes looks at his Airbus or his Boeing and wonders what it would be be like to perform a sweet barrel roll, or play leapfrog with the clouds. Just for fun. Then the fighter pilot gets firmly put back in his box and the pro pilot returns to another day in the cockpit. Or, as many call it, the office.

Maybe that explains why quite a few working pilots like to read my stuff. Rowland in New South Wales spent eight years flying in police helicopters, and he read his paperback Piece of Cake so often that it fell apart. He says: "Many of my vintage aircrew read it in our many and lengthy downtimes. We read parts of it to each other across the crewroom, office and hangar floor...Good memories." (He's now bought a hardback copy from me.) "A sincere thank you for the many hours of enjoyment Piece of Cake brought to very bored aircrew waiting for the telephone to ring." Robert in Cologne is another pilot (he's with Lufthansa) who keeps returning to Cake (now on his sixth reading). "For me, it is maybe the best book about flying fighters I have ever read," he writes, "apart from being a very good book." And he adds something it's always good to hear from a pro pilot: "You got the flying scenes right - and I'm very sensitive when it comes to that." But it's the humour and the characters that keep drawing him back: "I just read the part where Squadron Leader Rex elaborates on fighter tactics in October '39 - with Reilly (his dog) yawning and wandering away. That is so good." Dogs often make useful contributions in my books. My wife reckons that Othello, the elderly basset hound in Operation Bamboozle, has the best lines. Nobody hears him, of course, but he knows what he thinks.

Moving on: Gordon in Suffolk worked for Rolls-Royce engines until recently. He enjoyed Hullo Russia, Goodbye England, and he's not the first to tell me he's "absolutely appalled that you could not find a publisher. If you can't get this type of book published, who can?" It's a mystery to me too, but commercial publishers go their own sweet way, which is why I self-publish my stuff. Gordon, having found my website, says: "It was like discovering a treasure trove of undiscovered goodies." (He meant the books, not my author's photograph, which a friend said looks like a benevolent Balkans dictator. That's what friends are for.) Gordon passes on a story he was told by a veteran aerospace journalist who went to a reception given by a defence manufacturer. Many youngish MPs were there. The journo remarked to them that it was marvellous to see the Vulcan, greatest of all V-bombers, flying again. Blank looks. 'V-bombers....Vulcan, Victor, Valiant...Cold War... nuclear deterrent in the 1960s...' More blank looks. Gordon quotes Alan Bennett: "There is nowhere more distant than the recent past." Too true. It's one reason why I wrote HRGE. People forget. Even things like the motto of the nuclear powers - Mutual Assured Destruction - can slip their mind.

Readers continue to intrigue me by their sheer stamina. David in Barnes SW13 reckons he's read "just about every one of your books at least 5 times (beginning with Goshawk Squadron) and I have now recruited my present wife, my ex-wife, my two brothers, my daughter, her husband and soon, I hope, their two boys." To which, with the Cake DVD, he's just hooked his son-in-law. Truly amazing. John, somewhere in Oz, is reading Damned Good Show for the fourth time, and - because his dad flew in them - would like me to write about the dangerous, low-level work of four-engine Halifaxes dropping supplies to partisans in Italy, Jugoslavia, even Poland. Very hairy ops. And Peter in Ontario got a kick out of reading A Good Clean Fight, since his dad flew Kittyhawks with the Desert Air Force, went on to fly Spits in Johnson's Canadian wing at D-Day, and survived the war. Peter ("I'm a big fan") bought Hornet's Sting, Op Bam and Hullo Russia. Then Karen in Switzerland, having just read War Story and Hornet's Sting, says: "I loved both and 'missed' reading them when finished." She's always been interested in vintage aeroplanes and in photography (she sent me some fine airborne** shots taken at Old Warden, especially one of the Bristol Fighter), and her partner is a retired pilot. Add her interest in the history of both World Wars and (she says) "You managed to tick all the boxes that make the perfect book for me. I adored all the characters and found myself completely absorbed by the pilot psyche of the day." Lastly, Stephen in Nottingham "enjoyed Bamboozle, which managed to combine a page-turning plot with some lovely period detail (as ever), and a nice line in scams." He then raises an unusual point. In Cake, he says, I supply the background to every main character - except Moggy Cattermole. Stephen wants to know more about him. I'll give it some serious thought.

** If you would like to see Karen's pictures, Click HereReaders Write #10 March 2010

Humour can be more dangerous than gunpowder. With gunpowder, you get a choice of two: either it explodes or it fails. With humour, the choice may be three. Ideally, people laugh. But some people may not see the point. When that happens, the silence is deafening. And yet others may find the alleged humour so unfunny that, for them, it backfires. It offends them. This is the risk you take, because there is no such thing as a joke that cannot upset somebody, somewhere. So humour is a gamble. Ask any stand-up comic. He'll tell you of nights when he had to fight the audience to make them laugh. Other nights, they would laugh no matter what he said, even if it was "Corrugated iron". Humour is a battlefield.

Maybe that's why it's such a big ingredient in

my books. I write about battlefields (some of them in the sky) and

humour keeps

cropping up, even in the most desperate situations. It might be gallows

humour. In my first novel, Goshawk Squadron, a very

young

fighter pilot is so twitchy about going on patrol that he can't face

his

porridge at breakfast. Woolley, the CO, comes in. "Are you going

to

eat that,

Richard

Briers ('The Good Life') is one

of the best comic actors in

"My

fave is A Good Clean Fight,"

he writes. "Such vivid imagery!" He's a Flight Lieutenant,

RAAF, an Air Traffic Controller and amateur pilot, and his Aussie

grandfather fought tank battles in the Desert War (where AGCF takes

place), so it's no surprise that the book rang bells for

him. But

what strikes him especially is the humour. "Your wicked satire

style

is contagious, and I must control myself when dealing with difficult

people for

weeks after reading one of your books, lest I drop slightly too barbed

comments

in response to their 'unhelpfulness'."

Cut

to

Last

month I promised Stephen in

**************************************************************************************************

Readers Write #11 May 2010

Risky Hits, Inedible Cakes, and the shock of Woolley's Twin Brother

When

he was being interviewed on television, Stephen Sondheim remarked that,

at the

opening of

West Side Story on Broadway, many of the audience walked

out. The

show wasn't what they expected. Their idea of a good musical was lots

of easy

laughs, gorgeous girls, and songs you could whistle on the way home. West Side Story,

by contrast, was about love and hate between street gangs, and it

changed for

ever the way musicals were written. Sondheim (lyrics) and Leonard

Bernstein

(music) - with some help from Shakespeare -

wanted to

stretch their talents and challenge the audience's expectations.

They

wanted to move on, to create something fresh and new and surprising.

This

is satisfying but dangerous. Bizet's Carmen was fresh and new and

it got

panned by the critics. When Stravinsky's Rite of Spring was first

performed in

This

knowledge only goes to boost my respect for those big-hearted

readers who strongly recommend my stuff to their children, wives,

ex-wives,

working colleagues, neighbours, librarians, and someone they met in a

bar.

Peter, in

Some of the

emails I get rank me so highly amongst the Great Writers of

the World that I haven't the nerve to repeat them here. But Alan of W5

simply

says, "Big fan - keep doing it!" while D.E.W. in

The obit ran

in The Guardian on

22 March 1995 and it was

written by Christopher MacLehose (by far the best editor I ever

had). It

was for Edmund Fisher, a brilliant figure in the publishing world,

described as

"fabulously intolerant of dead wood" and "militantly

unpompous" and "a severe trial to his corporate masters".

MacLehose also detected "an inadvertent likeness in him to Major

Woolley,

the RFC commander in Goshawk

Squadron by

Derek Robinson whom Edmund later published (and what a terrifying

airman he

would have made): a brave, passionate, rebarbative officer,

always

seeking out the best in his men, a tireless inspiration to them, always

minding

about winning, having a huge appetite for combat, insufferable to his

superiors, a rattler of cages, a hater of pretentiousness and snobbery,

cutter

of swathes, not going to be forgotten."

Certainly not by me. Although he published Goshawk Squadron when he was at Sphere, I never met Edmund. My loss.

Readers Write #12 June 2010

Shot down by Rex, Lambs into Tigers

in

Some

actors say they get inside the skin of the characters they're playing

by first

mastering the way that character walks. I knew an actor like

that,

normally a charming chap but he couldn't get out of character during

the run of

the play; and sometimes that was rough on the family, especially when

he was

cast as a crude and selfish oaf. Every morning he would lurch

downstairs, slump

into a chair, curse the cat and demand a mug of tea in a voice made of

gravel.

Not easy to live with.

Actors live the part. When the TV series of Piece of Cake was

being

filmed on location, Tim Woodward - a pacifist in his

younger

years - played Rex, the squadron CO, a hard, ambitious and

arrogant

man. During a break in the filming I unexpectedly met Rex, in

uniform,

still looking hard, ambitious and arrogant. For a second, my

right arm

wanted to salute him. (I'd done my National Service, and you can take

the boy

out of the RAF but you can never take the RAF out of the boy.)

Woodward, as

Rex, looked right through me. Quite right. He was a squadron leader. I

was an

erk.

With authors, it's often names that help to create the character.

Rex was

perfect for the CO (we never know his first name). Before I could

begin Goshawk

Squadron I thought a lot about that CO's name, and until I

settled on

And

then there's Moggy Cattermole. I named him because he's lanky,

and it

helps if tall characters have long names. I knew someone at

school called

Cattermole, always nicknamed Moggy, and the combination seemed right

for

someone who is - as a

Which leads me to the Luis Cabrillo books, not so much lamb-into-tiger

as the

saga of Tell 'Em What They Want To Hear. It began with The Eldorado

Network,

inspired by the feats of a real double agent in WW2, codenamed Garbo.

He was

born in

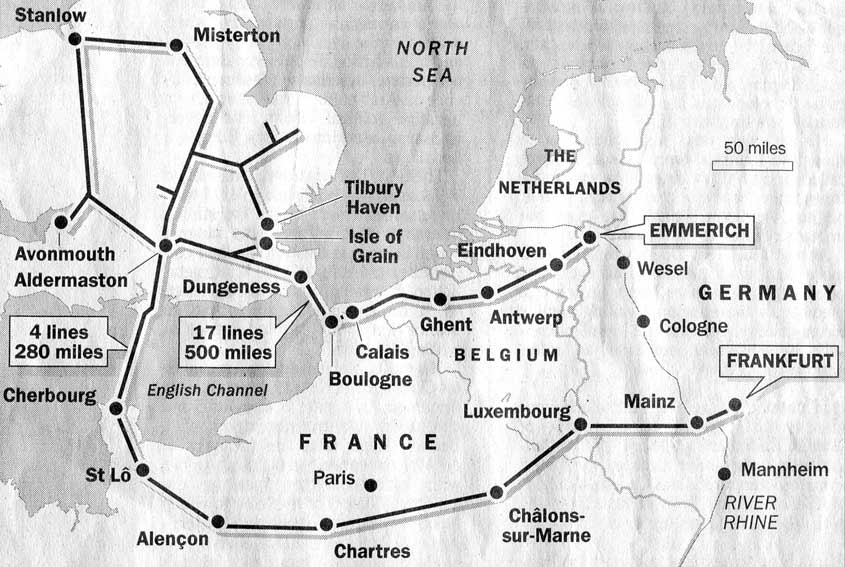

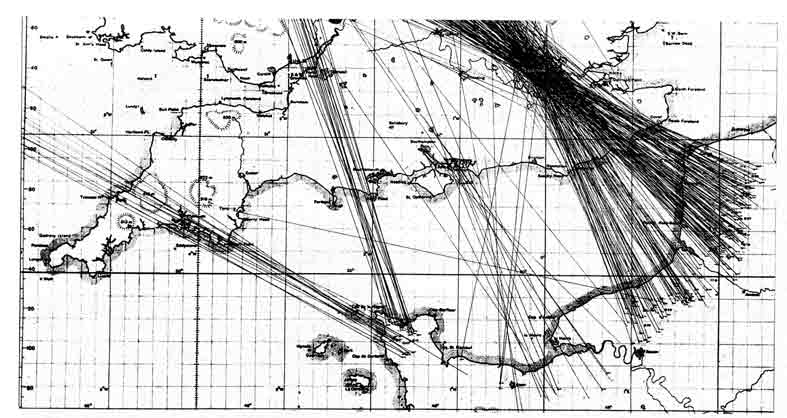

Enter a man who sees the true worth of Luis. Graham Thorne, of

"I

loved the classic Robinson opening paragraph, which brought me straight

into

the plot and made me want to know immediately what was going on. I also

loved

the headlong twists and turns of the plot and the fact that, for ages,

I could

not figure out what on earth the map on the cover had to do with the

book I was

reading.

The

rapid-fire and amoral style in which the book is written seems to me to

capture

perfectly what it would be like to know, and live with, Luis Cabrillo.

He has

immense charm and wit but also that whiff of danger - and

borderline lunacy - that makes us ordinary readers secretly

glad to

know him from a distance.

It

was

a joy to meet the gorgeous Stevie Fantoni again and a privilege to be

introduced to the Princess Chuckling Stream. Among the superb

supporting cast

of hoods and enforcers, I particularly liked the psychotic Vito

DiLazzari. He is the classic, indulged son of the tyrant,

over-educated,

so that he knows too much for his hereditary role -

Fox

instead of Hedgehog.

So

where now for Conroy and Cabrillo? I hope we hear more of them. For, as

Luis

gets older and that little bit slower, and as the world gets more

conformist

with less room for the maverick, then life for Luis will get steadily

tougher. Like a late Western, there is a great book to be written

about a

man running out of room, and Derek Robinson is the man to do it."

Well, time will tell. Are con artists an endangered

species? Recently,

an unemployed lorry-driver conned a property developer out of £1

million by

persuading him that the Savoy Hotel in

So: thanks to Graham, and to far-flung readers who recently asked for books - Anders in Sweden, David in Malaysia, Matt in Wisconsin, Fred in Virginia, Christopher in Spain, Lars in Denmark, Blair in Minneapolis, and many more.

Readers Write #14 September 2010

Readers Write #15 October 2010

Snoopy dies again, A quartet of Hurricanes, And never enough Cake.

Readers Write #16 December 2010

Caesar's slave rides again, Exploring the Canadian military, and a double whammy from the US.

Hanging on the wall of my bathroom is a message I got in the mail when the series based on Piece of Cake was on television. I got quite a bit of hate mail then, but this one was a classic, being not only anonymous but also written in crayon and all in capitals. It said:HAVE YOU EVER CONSIDERED TAKING UP MORE SUITABLE EMPLOYMENT?

LIKE BEING A BROTHEL DOORMAN.

TROUBLE IS, YOU MIGHT HAVE DIFFICULTY IN FINDING SOMEONE TO GIVE YOU A REFERENCE.

HANG ABOUT, THOUGH - HOW ABOUT A TELEVISION PRODUCER!!!

Not too subtle, perhaps, but I couldn't fault the writer for spelling or grammar, although a good editor might have queried the triple exclamation marks. I keep it on the wall for much the same reason that Roman emperors who were making a triumphal procession used to keep a slave standing behind them whose job was to whisper: 'Remember, Caesar, you are mortal.' In my case, the warning is: 'Remember, Robinson, some of the punters out there think your stuff is crap.'

And that's their

privilege. In the long run it's readers,

not authors, who decide whether or not a book makes the grade. I

mention this

because I get some very generous emails which may not be statistically

representative. Kieran in Buckinghamshire reckons that the RFC

trilogy is

'without doubt the best aerial combat books I have ever read'. From

Chris in

All that is on the plus side. I don't hear from readers who throw my book at the cat, say it's unreadable, and go down the pub instead. I don't hear from them because they're not going to waste a stamp on me, but I'm sure they exist. They probably won't read this, which is a pity because Chris Buckham, who is a major in the Canadian Armed Forces, found depths in the novels that surprised even me. He recommends that Junior Air Force Officers under his command should read them, and his analysis of Piece of Cake tells why:

'Dark humour underscores a theme throughout that speaks to the individual character's means of dealing with the realities of war. The strength of the book lies in its development of its characters and its insights into the human psyche. The Commanding Officers and Flight Commanders struggle with the changes that war brings in their relationships within the Squadron between themselves and the young line pilots. Conversely, the line pilots struggle themselves as they grapple with the deadliness of their chosen profession. Leadership strengths and weaknesses make themselves felt more keenly and shortfalls are quickly tolerated less or are forgiven. This novel captures the essence of the effects of combat on unit cohesion and command. It is stark and uncomfortable but it highlights lessons that are best learned and understood before the guns start firing.'

Which - as Chris points out - unfortunately doesn't always happen.

Finally, a double

whammy of praise in another unsuspected

place. John Sandford is an American novelist, much read on both

sides of

the

'The day was a nice one, the beginning of warmer weather, and the college girls were coming out of their winter cocoons, walking along with their form-fitting jeans and soft breast-clinging tops.

Excellent.

Maybe get a novel, Jake thought: he'd just read the first of a series of novels about British fliers during World War 1, by Derek Robinson, and was anxious to get another. And, of course, university bookstores were the most likely place to find his own books; like most authors, he always checked.'

(True. Jake finds a couple of his own books 'in what he thought was an obscure location', so he quietly reshelves them in a better spot. He also buys a copy of Goshawk Squadron.)

'With a sense of satisfaction, he walked across the street, got a bagel with cream cheese and sat on a bench in the sun and started reading about the Goshawks.'

Thanks, John. Always nice to get an unsolicited testimonial from someone in the same line of work.

********************************************************************************************

Readers Write #17 January 2011

Bristle with pride, The wide blue yonder in deepest Texas, and hilarity from Surrey to Florida.

Back in the days

when I was fairly broke, I came up with a

spoof glossary of the

dialect in my home town,

Krek

Waiter's

spawned half a dozen sequels. Today,

forty years on, it's still in print; and

if I'm known for anything in

Which reminded me

of what happened ten years ago, when the

British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterologists, Hepatologists and

Nutritionists met in

Life is full of

surprises. I had heard that copies of A Good

Clean Fight, my SAS and RAF novel set in North Africa, found their

way to

US Marines serving in

A different kind of

surprise came from Joe in Austin, Texas, who

- having read most of my

books -

was "excited to find your website" and decided to

download Hullo Russia from

Audible,

who supply Books On Tape. ("

Candidates for my Mile High Club keep appearing. Steve in Surrey, buying Red Rag Blues, says: "I've never read a book that even comes close to captivating me like yours do... I make a point of reading Piece of Cake at least once a year." And to prove it, he did something calculated to turn heads: "I laughed out loud on the train to work when I got to the point where Sticky reads out the cricket scores from the French radio truck." And there is similar laugh-aloud evidence from Edgewater, Florida, where Loraine writes that I'm her husband's favourite author, and she says, "I can always tell by the way he laughs that it is one of your books he's reading." (She bought Operation Bamboozle for him.) Alan in Wellington, New Zealand, bought Hullo Russia, having "recently done a mammoth re-read of all the RFC/RAF books and I loved them all over again." Penny,in Hertfordshire, a "big fan", wanted Hornet's Sting to complete her collection. And John in Portland, Oregon ("enjoyed many of your books very much") did the same.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Hornets in Yonkers, Hilarity and brutality in New Zealand, and Robinson-mania in the Netherlands.

You

may remember the report from a fan, deep in the American West, who

bought a springer spaniel pup, or it might have been a fox terrier, and

christened it 'Moggy', as a way of preserving the memory of that other

maverick creature, Flying Officer Moggy Cattermole in Piece of Cake.

(His girlfriend renamed the pooch to something she could shout in the

park without feeling embarrassed. Trapper, I think. Or

maybe Fang.

Now I hear from Jane, on

America's East Coast. She may qualify for my Double-Digit Club,

having read Goshawk Squadron

many times, and she adapts Woolley's

line: "Ah, bloody (insert name). I hate the bastard" when

she encounters bad drivers in up-State New York - and she

immediately feels better. Which just goes to show that fiction can be

powerful therapy.

More evidence of this from

an old friend, John Walsh (who actually lives in up-State New York).

He's teaching inner-city kids the basics of aviation by helping them

build model airplanes. As a way of developing a group allegiance, he

suggested they adopt a name, and so a dozen kids in Yonkers "call

themselves (very loud and very proud, by the way) Hornet

Squadron!". John is currently deep into my yarn of Hornet

Squadron, A Good Clean Fight,

for the third time. The book went with

him all through the second Iraq war and back, so it's no surprise that

the cover has fallen off.

Meanwhile, Tony in Nuneaton

put another of mine through its paces. He writes: "My copy of Kentucky

Blues has now been read by the whole family, including my

84-year-old

mother-in-law, who loved it as much as I did!" He bought copies

of Damned Good Show and Hullo Russia, Goodbye England. He

builds and

flies radio-controlled models and - perhaps inspired by

Goshawk Squadron -

decided to build an SE5a. Hendon air

museum let him take a close look at their RFC replicas. His

reaction: "Apart from the craftsmanship of it and all the other

aircraft, my overriding impression was of their frailty. Little

wonder the numbers shot down were far outweighed by accidents,

equipment failure and training." Too true. An excellent book on the

RFC, The First of the Few by Denis Winter (Allen Lane 1982) quotes the

official total of casualties at the end of the war: of 14,166 dead

pilots, 8,000 had died while training in the UK. No dual control

in those days. You were on your own, the first time you took

off. All too often it was your last.

They were young (18

or 19 was not uncommon) and the young laugh easily. So there was

humour to be found in every squadron - or, as Alan in New

Zealand sums up my war novels, "hilarious and brutal". Alan writes for

the Journal of the Wellington Science Fiction Society, but he casts his

net widely and it takes in non-sci-fi books as well. He's read

everything I've published and his review in the Journal of Hullo

Russia, Goodbye England - too long to print here in

full - is on http://tyke.net.nz

(go to 'wot i red' and then

go to February 2011). It's the first novel of mine to be set in a

time that he remembers. He was only a boy, but "I was nevertheless

strongly affected by the almost palpable sense of fear engendered by

the Cuban Missile Crisis. It seemed likely that the world I knew would

not be there when I woke up in the morning. If I woke up in the

morning."

And adds: "The thing that makes a Derek

Robinson novel stand out from all the others that surround it is his

impeccable understanding of history, his extraordinary ability to

re-live it in context through the eyes and minds of the people to whom

it is a contemporary happening, and the sharp, crackling and sometimes

breathtakingly cynical wit of his dialogue and of his observations; a

wit that is often laugh-out-loud funny but which makes you weep inside

even while you are laughing so very hard at the piercing truth of

it. Hullo Russia, Goodbye

England is a genuine tour de force."

Mail

arrives from elsewhere. Martin in SW6 has gone through all my books. He

read Hornet's Sting in the

office, "surreptitiously, almost under the

table" - even the most tolerant of offices might have

raised an eyebrow if he'd read it while completely under the

table. The image of the two Russian flyers in France, "playing

both the piano and poker fast and loose, demanding duels, has

remained with me for 10+ years." Now he's suffering what another

reader called 'withdrawal pains' and he asks urgently for "more needed

for the summer please!!" Well, I'm working on it, and I hope

something will appear in the summer, but - just as

Woolley predicted the war would be over by Christmas but which

Christmas he didn't know - I don't know which summer the

new book will be ready. I had a financial adviser called Lewis,

very good at his job, who used to ask me what I would earn next

year. I always said I hadn't the faintest idea, which caused his

brow to furrow. There are writerly types who crank out a novel a

year, fair weather or foul. If only. Goshawk Squadron took me

about nine months to write. (I was young and didn't know any better.)

Piece of Cake took four

years, and got derailed twice on the way.

Kentucky Blues was an idea

that refused to go away, but it took 25

years to germinate. How long will the new yarn take? As

long as it likes.

Paul in Deal discovered Piece of Cake

"when the children were young and to read half a chapter a night was an

achievement". Now they're off to University and he ordered

Hornet's Sting. Erwin in

Holland is one of my repeat offenders, having

read Cake for the 6th time.

He found a secondhand copy in the UK with

his girlfriend - now his wife - 20 years

ago. He's read all the rest ("wonderful books") and now

asked for Hullo Russia.

So did Joe,

three thousand miles to the west in Ramsey, New Jersey. He sends

thanks for my writing: "It puts me directly in a place in history I

never knew (I'm 30 years old), and is so rich and alive that I can

practically smell aircraft exhaust and fresh cut grass." Go back nearly

four thousand miles to the east, where Stian in Rogoland, Norway. wrote

his master's thesis on WW1 aviation and got "much enjoyment"

from Goshawk Squadron, so he

asked for the prequels, War Story and

Hornet's Sting. He served with the Norwegian Army, and says: "You

describe service culture quite well." Well, the military is the

military wherever you go. Streaking south by ten thousand miles

takes me to Steve in Te Anau, New Zealand. He found the same

satisfaction as Stian: "I'm ex-RAAF, so I could relate to the military

BS between squadron and upper echelon - it still goes on."

Of Goshawk Squadron he says:

"I couldn't put it down, really enjoyed

the banter between pilots and the black humour, interlaced with vivid

dogfight scenes." Zooming up to the USA and Michael in central

Indiana ("currently reading A

Good Clean Fight for the 10th

time") works in community theatre and would like to adapt my RFC

trilogy for the stage. I'm happy to give the project my

blessing.

Finally, how about this...

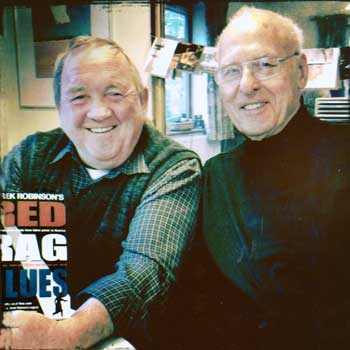

I'm

the guy in the glasses and the slightly worried smile on the right. The

guy with the cheery grin is Bill Hitchings, confident that his camera

is doing its stuff. Bill flew from Melbourne (reading Damned Good Show

on the flight - "just as enthralling" as my other

books) and he dropped in for a cup of tea. Good to

meet him.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Going where no university dared, Matching Woolley Guinness for Guinness, and the Agony Aunt Flies Again.

What

sort of book is Goshawk Squadron?

One family read it and the

husband thought it was a great adventure, his wife found it a moving

love story, and their teenage son laughed his socks off. I think each

was right - it's a story of young men who fall in love when

they're not fighting for their lives, and make the blackest of jokes if

they survive.

As it was my first novel,

people sometimes ask me why I wrote it. Was it for the combat, or

the romance, or the humour? The answer is all of those and more. I

wrote it for the history. Nobody had written a brutally honest book

about the Royal Flying Corps and I wanted to fill the vacuum. I

wrote it for me, and if anyone else liked it, well, that would be

a bonus. Luckily for me, the bonus happened and Goshawk still

gets readers all over the world.

I realised

the wider truth about that vacuum when I saw a review by David

Aaronovitch of a book called 'Civilisation'

by Niall

Ferguson. One cause of the recent economic disaster, so

Ferguson claimed, was that few bankers knew anything about the 1929

Crash, and he blamed that failure on the last 30 years of

education. Aaronovitch shot that notion down in flames.

When he studied modern history at Oxford 35 years ago, he said, nothing

after 1914 was taught. He got Gladstone but not the Depression.

Same happened to me when I was studying history at Cambridge in the

Fifties. The biggest events of the century, the two World Wars, were

out of bounds. But they had influenced everyone's lives,

including mine, and they were exactly what I wanted to understand.

Later, when I could, I researched them. And wrote some books. My

fiction is based solidly on fact. The stories may be ripping yarns, but

they're also reliable history.

And if a reader prefers the yarn

to history, that's fine by me. Darren in New Zealand writes

that he gets unusual satisfaction from Goshawk. He "acquired a copy

25-odd years ago in a pub in South Wales after a bollox-freezing game

against some feral team from the valleys. I've carted that book around

ever since. To add a bit of realism to the story, every time Woolley

reaches for a Guinness, I do the same." The first chapter

is a bit of a challenge - Woolley sinks a few -

but "after that it's downhill all the way." Amazing.

Equally

impressive are the model-makers. Keith in Leeds bought a copy of

A Good Clean Fight. This

is a sequel to Cake,

and it

follows Fanny Barton and his Hornet Squadron in the Desert War, where

they fly the P40 Tomahawk. Keith plans to build scale models, and

asked my permission to use my initials as squadron recognition letters

on the planes. I'm flattered. And Peter in Nottingham

bought Cake and Hullo Russia, Goodbye England (he

describes himself as

"a complete Vulcan nerd - I've been in the cockpits of six

of the survivors"). He's a semi-pro in the model business

- he's sold a few of his WW2 tanks to film companies

- and, inspired by A Good

Clean Fight, he's not only built models

of the Tomahawk but also photographed them flying low over the

desert. Look closely and you might see the shark's teeth on the

nose. Very convincing.

What

next? I'm Stone Age Man when it comes to the more exotic workings

of the Internet, so the doings of Steve in Victoria, Oz, leave me

gasping. He bought Hornet's

Sting (thus completing his

trilogy) and told me that he and a group of like-minded

enthusiasts are "flying Rise of Flight (a WW1 flight sim) over the

Internet". Actually flying? "Check us out on Oceanic Wing ,"

Steve suggested, so I did. These guys recreate

WW1 aircraft (and others) that are so realistic that they can fly

(and fight) them. Astonishing. Their website also has a books

page with some enthusiastic remarks about my stuff, so they're

obviously well-read too.

A quick whizz through

other mail. Christine in Southampton was stumped for something to give

her ex-RAF dad on his 89th birthday, and then found that he'd read my

Damned Good Show and was

"completely blown away by how authentic and

realistic your book is". So she bought him a copy of Cake and one

of Hullo Russia.

Problem solved. Leon in Woking also

bought Hullo Russia,

and added that Cake "remains

for me the

perfect novel in terms of content, pace, characters, dialogue, depth,

everything!" and urges me to keep writing. Well, I do my

best. John in Japan bought an armful of books and asked:

"Why on earth hasn't War Story

been either made into a movie or

televised?" Good question. The movie/TV business is a total

mystery to me too. Howard in Santa Cruz, California, had the

initiative to email my new publisher and tell him that printed editions

of some of my books "are available only in the range of $100" and

he urged him to issue all my stuff as eBooks - which,

in fact, my publisher is now in the middle of setting up.

(100 bucks is a crazy price, brought about simply by the fact that some

books are scarce. At one stage, specialist book dealers were asking

over £200 for a used copy of Hornet's

Sting - which is why

I decided to self-publish it for a fraction of that price.) And finally

Steven, I don't know where, tells me that years ago he bought A Good

Clean Fight, couldn't get into it, threw it down in disgust (too

young

to appreciate it, he thinks), picked it up later and loved

it - especially the relationship between

Schramm and Maria Grandinetti. As a result, he says: "I've always

promised myself, in the event of a lady deciding to 'love me for five

minutes', to take the bull by the horns." Go for it, Steve.

You never know. Five minutes could last a lifetime.

The roller-coaster of books, Shock-horror at MGM, and mobilising the mental juices.

Computers get a bit of

stick nowadays for what they do to

reading and writing - everyone is stuck to the

screen, so

it's said, and nobody writes a real letter any more. But there's

another

angle. The Internet has been good for books (if not for

bookshops). Peter

in Toronto tells me that, 19 years ago, "My father introduced me to Goshawk

Squadron when I was 13" (a round of applause for fathers like

that)

"but I only just started reading your other novels, obtained secondhand

or

over the 'Net, as most seem to be out of print." Too true, but

I'm

leaning on my publisher to revive them. Peter ordered copies of Hornet's

Sting and Hullo

Meanwhile, a longtime fan, David in Malaysia, tipped me off to something my publisher had failed to tell me, which is that their reissue of Piece of Cake and Hullo Russia, Goodbye England has been postponed from this October to next February. There's a reason: the designer we had lined up to create the new covers dropped out and so we're starting from scratch. Book covers are what the Promotion Department needs in order to do their job. One bit of good news: you can now get (if that's your taste) my RFC trilogy (War Story, Hornet's Sting, Goshawk Squadron) as e-books on Amazon/Kindle. Swings and roundabouts. Or snakes and ladders. Maybe ham and eggs. Take your pick.

The moral of the story, I suppose, is to soldier on and hope the good and the bad luck even out. Take the case of the American Hugh Martin, a nice guy and a talented lyricist and composer. He died a few months ago, aged 96. During the Second World War he co-wrote several hits, including a number called The Trolley Song ('Clang, clang, clang went the trolley, Ding, ding, ding went the bell, Zing, zing, zing went my heartstrings. From the moment I saw you, I fell...') which, if you're one of the younger fellahs, you may never have heard. But in 1944 Judy Garland belted it out in the movie Meet Me in St Louis, and it helped make her a star.

Hugh Martin kept

working and in 1957 he had another

hit. Bear in mind that by 1957 the world looked a grim and gloomy

place.

The Korean War had ended in stalemate. Nuclear tests were exploding in

all

parts. The Soviet Union had the first satellites circling the globe,

including

the

Have yourself a merry little Christmas,

It may be your last,

Next year we may all be living in the past.

The studio turned it down flat. Bittersweet and nostalgic they might accept, they said, but not a dirge. Martin got to work and rewrote the last two lines:

Let your heart be light;

Next year all our troubles will be out of sight.

And of course

Martin lived to see his song become as

immortal as anything can be in showbiz. Was he sorry to lose the

lines

which he felt had expressed the world in 1957? Probably.

But he was

a professional. He was in the entertainment business. So am I.

First and

foremost, I write novels that entertain. If they also take the

reader

somewhere he might never otherwise have gone, and make him think

a

little - what the film director Sidnet Lumet

called

"stimulating thought and setting the mental juices flowing

" - well, that's a bonus. Lumet managed it

in

such fine movies as Twelve Angry Men, Network and Dog Day

Afternoon. Whether I manage it is entirely up to the

reader, but I'm

encouraged when I hear from Peter in Portishead (the town, not the

band) who

first read Goshawk Squadron as a boy, "while hunkered

under

the bedclothes with a torch." Since then it's been with him in

the

first Gulf War,

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Readers Write #21 October 2011

Literary lions stumble, Confessions of an invisible man, And explosions of brilliance in Dublin

Why do writers

write? I ask because Bud, in

And a different

author. I'm not the same scribbler I

was twenty, thirty years ago, and what may seem worth exploring

now was

unknown territory then. As someone once said: How do I know what

I think

until I see what I've said? Except that, in my case, I

often don't

know what I've said until you, the reader, points it out to me.

Every

novel is a gamble, and even the best writers stumble, once in a while.

Robert

Louis Stevenson and P.G.Wodehouse - two names you rarely

see in the

same sentence - each wrote a stinker or two. They

must have

thought the yarns were a good idea at the time. (Nobody sits down

and

thinks: I'll waste a year or two on a real turkey.)

But the

end product was a big mistake. OK, if you insist, I'll tell you

the

titles: Stevenson's Catriona (poor sequel to Kidnapped; David

Balfour falls in love with the childish Catriona who, as Stevenson

admitted, is

"as virginal as billy-ho!") and

Back to the beginning. Why do writers write? Bill, somewhere in the US, came across Piece of Cake in the library of the US Naval Hospital in Portsmouth, Virginia, enjoyed it immensely, cruised through my RFC and RAF series and, he says, "to some modest degree, they shaped the man I am today." He's seen life: after the Navy he became a paramedic and a firefighter. He adds that "Frankly, after my father, you and Bernard Cornwell have been my biggest and most positive role models." I was startled. I take what you said as a compliment, Bill, but I'm not sure I'm comfortable being a role model. After all, I'm the invisible man in the room. I just tell the story and let the reader make what he likes of it. Two characters I've invented - Stanley Woolley in Goshawk Squadron and Moggy Cattermole in Cake - are not the sort of men you'd want your daughter to marry. Yet they score strongly with readers. I don't know where I found them. Sometimes I think the door was left open and they wandered in. That's how Skull arrived in Cake (and other books). They're all lucky accidents. But role models?

It's easy to say why writers don't write. Not for the money. Writing novels is a precarious business. The Inland Revenue taxes me by estimating what it reckons I'll earn next year, which is total guesswork based on what I made last year. Like most freelance writers, my income goes up and down like a roller-coaster, so the Revenue get it wrong as often as right. If you want steady money, I'd recommend a career as a chartered accountant.

What about

fame? It's not much of a reward. It

certainly won't pay for the groceries. A good review in the newspapers

is very

welcome, as long as you remember that it'll wrap tomorrow's fish and

chips.

Fame is fleeting, and so are novels. Nearly all the heavyweight

bestselling authors who dominated the fiction lists when I was a boy

are out of

print now and largely forgotten. Will my stuff be around fifty years

from

now? Do I care? Not much. I'm not writing for posterity (it

never

did me anything for me). And look at what happened to J.M.Synge, who

wrote The

Playboy of the Western World. The play's opening night, in

Synge's crime was

to write a play without Irish

heroes.

Quick round-up of

my mail. Jim in

And Ben, now in his final year at school, having not only read my RFC trilogy but also got his mother and mother to read it - "an achievement of sorts" - is writing a 5,000-word project as an A-Level extension. His subject: Hitler's Operation Sealion and the truth about the role of Fighter Command in the non-invasion of 1940.....a topic I've looked at in my Invasion 1940. Meaty stuff.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Readers Write #22 January 2012

Ice cold

in

The Royal Flying Corps is almost a hundred

years old. A reader of my RFC trilogy today is in a comparable position

to

someone in 1912 who was reading about the

Somewhat north of

Perhaps. But if Sealion had sailed in a

flat calm, the Royal Navy was ready and waiting.

Europeans are often so fluent in English

that they put us Brits to shame, and Boris in Frankenburg,

Leap ten thousand miles to the south-east

(which of course is no barrier to the Internet) and Liz in

Now jump another few thousand miles to

From

One thing is definite. I shan't be doing any business in all of February 2012. The shop will be shut while the computer gets thoroughly overhauled, oiled and polished. So - please save your emails for March.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------A curtain-call for extras, gunplay in the bathroom, and laughing fit to bust

The folk-singer Fred Wedlock, now alas no longer with us, once told me the secret of how to create a statue of a horse. "Get a big block of stone," he said, "and hack off everything that doesn't look like horse." There are days when writing feels like making that statue, except that the chisel is blunt and the mallet has a handle made of rubber.

That's when I

reach for my omnibus edition of Raymond

Chandler's novels, partly for the pleasure of seeing a champion in

action,

partly to remind myself that he had his bad days too, and partly to

remember

that what matters (especially in a crime story) are the extras, the

minor

characters whom Chandler crafted so beautifully. In The Lady

in the

Lake, he has a scene where his private eye Philip Marlowe visits

the

Graysons, a retired couple who can probably provide some

information.

'Grayson was a long stooped yellow-faced man with high shoulders, bristly eyebrows and almost no chin. The upper part of his face meant business. The lower part was just saying goodbye. He wore bifocals and had been gnawing fretfully at the evening paper.'

There is another link.

It goes back to long ago, when Hamish

Hamilton was publishing The Eldorado Network. By good

fortune, Roger

Machell was my editor - and Roger had also been

Raymond

Chandler's editor for his British editions. He told me that one day his

phone

rang and it was Chandler, calling from his home in La Jolla,

California, and

obviously very drunk. "I'm going to shoot myself," he said.

Roger, thinking fast, said, "Don't do that, Raymond. Let's talk about

it..." He heard two loud bangs. Then silence. Roger phoned the La Jolla

police, they hurried over and found

End of anecdote. But

what interested me was that when

Thanks to the Internet,

I get echoes of what I write in

emails from readers all over the globe. Of course praise is

encouraging.

(There is no limit to the flattery an author can absorb.) Bill,

somewhere

in the

John in

Then - surprise, surprise - a letter from Guy, a very old pal (we were at college together, back in the Middle Ages). Recovering from a rather nasty illness, he had time to re-read my flying stories - 'Once again I was totally engrossed among the vivid characters. Their persuasive arguments and caustic banter make them so alive and such good company.' Enter his wife, to give him a copy of my non-fiction book, Invasion. 1940, and he says 'to my astonishment I was so hooked by the reasoning that I finished the whole of it before returning to the interrupted novel.' Well, I worked hard to make that slice of history as readable as any work of fiction, and I'm glad it paid off. Guy spent his National Service on a Motor Torpedo Boat, dashing up and down the Channel, so he has personal knowledge of those hazardous waters.

I'm delighted to hear that Guy's gremlins have been zapped. On the other hand, maybe the Luis Cabrillo quartet should have a health warning on the cover. L.L in New York 'picked up Red Rag Blues, ran across Cabrillo, the Fantonis and Chick Scatola (Mafiosi of varying competence) and began laughing so hard' that he ended up in hospital - although it's only fair to add that he was already suffering from a deep chest cold, so maybe Luis Cabrillo's con-artist doings simply hastened the doctor's decision. Anyway, I sent L.L. a copy of the sequel, Operation Bamboozle and he replied with thanks, saying: 'I look forward to reading BAMBOOZLE with a pacemaker handy.' Both books were fun to write, and I'm glad they're fun to read.

My thanks to all who wrote, and to the many who sent me birthday greetings on Facebook - too many for me to answer. Plugs, Black Eyes, And Other Occupational Hazards

Critics

are readers, too. At least, some are. I've known book

reviewers who, pressed for time, just read the publisher's blurb on the

back cover. Othere, with a little more time, glanced at every

third page of the book, which they reckoned was enough to give

them a feeling of whether or not it was any good. They have my

sympathy. I've done their job myself, and it's a daunting

prospect when you get given four or five thick books, all to be

reviewed by next Tuesday.

That's

why I value the advice of the best literary agent I ever had, the late

George Greenfield. "Don't read your reviews," George said. "Measure

them." Size equals impact.

Nevertheless,

I did read them, if only to spot the mistakes. I remember a

rather sniffy (but quite large) review of A Good Clean Fight

by a man whom I knew to be an academic. He ended his piece by

saying that I was shaky on jargon in the Desert Air Force, and

that "the knowing reader" (meaning himself) "waits in vain for the

squadron's Kittyhawks to be identified as 'Tommy Dodds'." Well, I

research my books pretty thoroughly. I wrote and told him I'd

never come across this nickname, so what was his source?

He

apologised. He'd got it wrong. He had looked in The Concise Dictionary

of Slang and Unconventional Usage and he'd misread the entry. It

happens. I chalked it up to experience.

Authors

who get steamed-up by bad reviews are like actors who storm about bad

notices - too sensitive. After all, it's only one

man's or woman's opinion, and (as I've often said) no book is for

everybody. My first novel, Goshawk Squadron, got

some good reviews and some very bad ones. A respected writer in an

eminent magazine read Goshawk and his review advised me to

quit now and find a better job, such as digging ditches. My local radio

station asked Alan Gibson to review the book. He'd won a Double

First at

Take

away Woolley and the book vanishes. If Woolley had been simply a

four-letter word, he would be shallow and tedious, and the book

wouldn't be worth reading, then or now. Yet, in

the years since Alan's review, there have been at least six

editions of Goshawk Squadron and several

translations. MacLehose Press will bring out a new edition later this

year.

Moving

on from Goshawk Squadron to Piece of Cake. It was

widely reviewed in

"Robinson's

characters are not much more than his historical revelations," he

wrote. "The cast consists of cliches." And he spelled out what he

most disliked: the pilots are "virtual subversives and

delinquents, sarcastic wits skilled at insubordination, drunken,

sadistic, nutty, scared to death, welcoming as an inestimable

benefaction every day clouded over and unfit for flying." Not the

book I remembered writing. And his account was odd, because

later Fussell found fault with the way I 'romanticized' the squadron:

"No group of pilots could be so charmingly intelligent and verbal, so

gifted at Noel Coward repartee..."

It

puzzled me that Fussell could wish to have it both ways, finding the

pilots so repellent yet so charming.And my guess is that one reason why

Piece of Cake has been reprinted so often, and is now

reissued by MacLehose Press, is that Fussell totally misunderstood the

book. Readers like the characters he hated; they even like

dodgy types like Moggy Cattermole. They enjoy the humour. Former

RAF aircrew tell me that the dialogue is convincing, that

aircrew banter was very like mine (and still is). As a

history of the first year of WW2 in the air, the book is accurate and

authentic, but what brings readers to return to it again and again is

their recognition of the characters, of their enjoyment of life and the

abrupt fact of their death.

Well,

Fussell's review was a long time ago, and now he too has died, on 23

May 2012, aged 88, an acclaimed literary scholar. In 1944 he fought

with the

By

coincidence, as I was writing this column, an email arrived from

an old fan, Martin in the

Thanks also to Robert in Texas, Max in East

Sussex, John in Edinburgh, Chris in West Australia, Jonathan in Surrey,

and Sam in Devon - and to everyone who wrote.

Stooging down The Mall, Strafing the literary festivals,

and Moggy on the analyst's couch.

Readers Write #26 September 2012

No Bananas, radiant seagulls, and stoked in the USA.

In my last RW, I took a poke at literary festivals and how they distract writers from the business of writing, so this time I'll have a go at mega-hyper-super-bestsellers. Friends - intrigued by the soaring runaway sales of the Grey trilogy - have asked me how I feel about it. Depressed? (Why not my book?) Elated? (Bookshops full of punters.) Astonished? (Nobody saw it coming.) None of the above.

Freaks happen. Back in the 1930s, someone wrote a song called Yes, We Have No Bananas. It swept the country. People were singing it everywhere Music publishers must have looked at each other and said 'No Bananas is a hit? World's gone crazy.' Well, every now and then it does go crazy, and publishing is no exception, especially when word-of-mouth gets into the act. Many years ago, a New York publisher put out a novel called Jonathan Livingstone Seagull. Without enthusiasm, and with no hopes of making a dollar from it, because the story was about a bored seagull who seeks perfection in flight and finds wisdom, together with two other radiant and loving seagulls. Well, somebody liked it, told his friends, and the rest is history. Also economics, because Seagull not only topped the New York Times Best Seller List, for two years it was the best-selling book in the USA. It became a movie. (Neil Diamond sang the songs.) Critics panned the book - one said that, by comparison, The Little Engine That Could was 'a work of some depth and ambition' - but who cared? It was everywhere. It was a freak. These things happen.

In fact they've been happening ever since the 1890s, when publishing stopped grinding out three-volume sagas to amuse the rich and idle and began offering cheap fiction to the masses. The sales of Mrs James's Grey trilogy aren't particularly huge, compared with the scores racked up by the literary giants of Edwardian times and the years between the wars. When Edgar Wallace was going strong, it was reckoned that, apart from the Bible, one in four books bought in England was an Edgar Wallace thriller. Ethel M.Dell, the Mills & Boon of her day, almost matched him. But for really big money and colossal ego, nobody got near Marie Corelli. In the 1900s, her novels earned her (in modern money) a million pounds a year, and she had the longest entry in Who's Who. She lived at Stratford-on-Avon in a style that makes our own dear Barbara Cartland seem like a shrinking violet. Marie had a coach pulled by two Shetland Ponies, in which she progressed around Stratford every day, with the coachman perched above and behind . Her Venetian gondola took her on the Avon, with a genuine Italian steering it. Why not? The eggheads said her books were sentimental junk, but she claimed to be the most widely read writer, in English and in translation, in the world. And she probably was.

But not forever. In 1908, Hall Caine's novel was (he said) the first to sell a million copies in Britain; and then came Nat Gould's prodigious output - 130 novels, all about horse-racing. By 1927 he'd sold 24 million copies and was still going strong. Corelli had fame, but Nat had more readers. So where does the Grey trilogy slot into this pantheon? Modestly, when you look at (for example) Terry Pratchett's 45 million sales - and he's just one of many in the record books. Thomas the Tank Engine has sold 200 million copies. So has Enid Blyton's Noddy. Erle Stanley Gardner's Perry Mason books have reached 300 million. J.K.Rowling's Harry Potter series tips the scale at 450 million. Vast forests have been felled to make the paper for these blockbusters. So why don't I feel jealous? Two reasons.